9 July 2016

As you are eating a piece of chocolate, do you take the time to pause and truly savour the moment? To allow your tastebuds the opportunity to be tantalised by an explosion of different flavours and your palate to be caressed by the smoothness of the chocolate as it melts at your body temperature?

For those of us that do, we may truly appreciate the beauty of “bean to bar“. I’ve mentioned the term “bean to bar” on several occasions throughout my posts. What does it really mean and why is it important anyway?

To put things in perspective, let us start from the very beginning – the cocoa plantations deep in the tropics and sub-tropics. Here, the cocoa pods or cabosses are harvested by hand to preserve the integrity of its precious beans. The cocoa beans within the pods are carefully extracted, along with the moist, fibrous, white pulp that envelops the beans. The beans are then laid on banana leaves and covered, or placed within closed bins or boxes. Nature takes its course, whereby the combination of moisture, heat and airborne microorganisms results in the fermentation of the pulp into alcohol. The alcohol is further oxidized to lactic and acetic acid, by gently aerating the beans. The reaction between moisture, alcohol and acids leads to initial flavour development of the beans. This fermentation process is allowed to occur for up to 8 days, after which the beans are sun or air dried, sorted, bagged and ready to be transported to chocolate manufacturers around the world.

At this point, the “bean to bar” journey begins.

The Bean

Batches or bags of cocoa beans arriving at manufacturing plants are thoroughly checked and tested. Once the seal of approval is given, the beans are cleaned then roasted, much like coffee beans. Roasting causes the cocoa beans to develop their characteristic aromas, flavours and colours, which may be unique to their variety, plantation and country of origin.

‘”Bean to bar” chocolate makers may apply their own method of roasting the beans to accentuate its desired characteristics.

The Cocoa Nib

During the roasting process, the shells of the cocoa beans separate from the kernels. The de-shelled kernels are more familiarly known as cocoa nibs. The cocoa nibs are winnowed by air, or using sieves or filters, to completely liberate the nibs from the shells.

During the roasting process, the shells of the cocoa beans separate from the kernels. The de-shelled kernels are more familiarly known as cocoa nibs. The cocoa nibs are winnowed by air, or using sieves or filters, to completely liberate the nibs from the shells.

The Cocoa Liquor

The pure cocoa nibs are ground or milled to produce the cocoa liquor. During this phase, depending on the type of chocolate to be made, ingredients such as sugar, lecithin, milk or milk powder and vanilla may be added to the cocoa liquor. The cocoa liquor mixture is then refined.

“Bean to bar” chocolate makers may apply their unique refining method, grinding to different particle sizes or degrees of fineness to achieve the desired smoothness and mouthfeel of the eventual chocolate. They will typically also adjust the chocolate formulation by adding or removing cocoa butter and other ingredients to produce the intended taste, flavours and type of chocolate (i.e. white, milk or dark chocolate).

The Working Chocolate

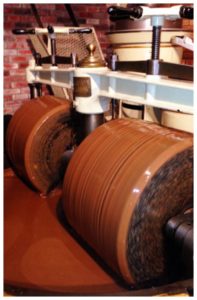

Next, the cocoa liquor mixture is subjected to conching, which is regarded to be the all important step in the development of the flavour, smell and texture of chocolate. The mixture starts as a powdery mass and is kneaded using a machine known as a conche, for a period of several hours to several days. The continuous motion further refines the texture of the mixture and promotes flavour development through a combination of evaporation of volatile chemicals and acids, and oxidation. The end product is the working chocolate.

Next, the cocoa liquor mixture is subjected to conching, which is regarded to be the all important step in the development of the flavour, smell and texture of chocolate. The mixture starts as a powdery mass and is kneaded using a machine known as a conche, for a period of several hours to several days. The continuous motion further refines the texture of the mixture and promotes flavour development through a combination of evaporation of volatile chemicals and acids, and oxidation. The end product is the working chocolate.

“Bean to bar” chocolate makers vary the duration of conching to achieve the desired flavours and texture in their chocolates.

The working chocolate is then usually tempered to create the characteristic “snap” and glossy shine of finished chocolate. Tempering chocolate involves putting it through a cycle of heating and cooling to align fatty acid crystals in cocoa butter, and to maximise formation of the desired beta crystals. Tempering also prevents the formation of chocolate bloom, the whitish film, streaks or spots of cocoa butter that are sometimes seen on the surface of chocolate.

“Bean to bar” chocolate makers may use one of several methods to temper chocolate, namely seeding, tabling and machine tempering.

The Bar

Tempered chocolate is now ready to be moulded into bulk bars, which may then be re-tempered to make finished chocolate bars, blocks, pralines and other moulded chocolates. The tempered chocolate may also go into another production cycle to produce buttons, pellets or blocks of couverture chocolate (which may sometimes be untempered).

Tempered chocolate is now ready to be moulded into bulk bars, which may then be re-tempered to make finished chocolate bars, blocks, pralines and other moulded chocolates. The tempered chocolate may also go into another production cycle to produce buttons, pellets or blocks of couverture chocolate (which may sometimes be untempered).

Couverture chocolate is the starting material used by chocolatiers all over the world to create masterpieces of dipped, moulded or coated chocolates, and chocolate sculptures.

Both “bean to bar” chocolate makers and chocolatiers apply their creative flair to bulk chocolate to develop their eventual artisanal works of art.

Now, let us revisit the questions at the start.

What does “bean to bar” really mean? I trust that this has been clearly explained as we went through the intricacies of the chocolate making process.

What does “bean to bar” really mean? I trust that this has been clearly explained as we went through the intricacies of the chocolate making process.

Why is it important anyway? I feel that it’s important to appreciate chocolate making as an art and skill, not just a process; there are many steps where “bean to bar” makers can impart their different and creative variations to produce unique tastes, flavours and textures of chocolate. It is also pertinent to understand the distinction between a “bean to bar” chocolate maker and a chocolatier, although I believe that the former is none less skillful than the latter.

So next time you eat a piece of chocolate, pause and savour the wonderful aromas, flavours and textures in your palate, and spare a thought for all the effort that has gone into its creation, from “bean to bar”!