23 July 2016

Imagine this: You are driving along a quiet country road. Apart from the abundance of greenery, you see the occasional oncoming car, heavy vehicle and a die hard cyclist or two. Along the way, you pass tired looking stone houses, sometimes abandoned, a smattering of fuel stations, and the odd shop and local eatery. Then suddenly, you come upon a scene that is more reminiscent of a bustling city. A classy shopfront with glossy windows, adorned with vibrant and attractive displays of chocolate in every shape and form.

This was the scene that greeted us as we arrived at the headquarters of Andrea and Daniele’s family business, situated just outside the Tuscan town of Monsummano Terme. Originally established by their father, Luciano, as a specialty coffee roasting business, Andrea and Daniele subsequently took over the reigns and expanded the business. Daniele further honed his expertise in blending and roasting coffee while Andrea decided to build on his fascination with chocolate, applying his artistic and creative flair. These days, Slitti Cioccolato e Caffe (chocolate and coffee) is well reputed not just in Italy, but as far away as Asia and Australia, for their quality, award winning chocolates and coffee.

This was the scene that greeted us as we arrived at the headquarters of Andrea and Daniele’s family business, situated just outside the Tuscan town of Monsummano Terme. Originally established by their father, Luciano, as a specialty coffee roasting business, Andrea and Daniele subsequently took over the reigns and expanded the business. Daniele further honed his expertise in blending and roasting coffee while Andrea decided to build on his fascination with chocolate, applying his artistic and creative flair. These days, Slitti Cioccolato e Caffe (chocolate and coffee) is well reputed not just in Italy, but as far away as Asia and Australia, for their quality, award winning chocolates and coffee.

Excitedly (despite the “no photographs” sign out the front), I push open the front door and walk in. Immediately, I am greeted by the heavenly scent of chocolates, and the addictive aroma of roasted coffee beans. What more could one ask for at breakfast? The set up is rather clever. There is a retail section out the front, of all of Andrea’s artisanal chocolate bars, tortinas, panettos, girottos, powders and spreads plus a glass showcase displaying his handcrafted pralines, truffles, giandujas, ganaches and rochers, next to a section showcasing Daniele’s selection of roasted coffee beans. To the back is a small cafe, serving Slitti’s selection of coffees and hot chocolates, and a range of sweet and savoury treats. One wall of the cafe is decorated with shelves of books – on nothing but chocolates and more chocolates! I totally get it?

Curbing my enthusiasm for the chocolates that are still to be discovered, hubby and I head straight to the cafe section for breakfast. We place our order for a caffe marocchino and hot chocolate respectively.

Curbing my enthusiasm for the chocolates that are still to be discovered, hubby and I head straight to the cafe section for breakfast. We place our order for a caffe marocchino and hot chocolate respectively.

A caffe marocchino is coffee with a dash of hot chocolate, topped with frothy milk and sprinkles of cocoa powder or chocolate shavings.

And to keep with the Italian breakfast tradition, we throw in a sweet treat of custard croissant.

A typical Italian breakfast generally comprises a hot beverage, usually coffee, and a sweet pastry or bread.

The hot chocolate is delectable. Warm and rich chocolatey goodness, with just the right amount of sweetness. The texture is pleasant and the consistency is thick but not viscous. It hits the spot.

Once sated, we adjourn to the retail section. Where does one start? Systematically, I begin with the award winning ones. The Tavoletta d’Oro (Golden Bar) is acclaimed as the most important chocolate award in Italy, and as a testament to his mastery, Andrea has won a Golden Bar for different creations almost annually since the 2000s (sometimes for the same product over multiple years). He has also been celebrated at the International Chocolate Awards and Salon du Chocolat.

Once sated, we adjourn to the retail section. Where does one start? Systematically, I begin with the award winning ones. The Tavoletta d’Oro (Golden Bar) is acclaimed as the most important chocolate award in Italy, and as a testament to his mastery, Andrea has won a Golden Bar for different creations almost annually since the 2000s (sometimes for the same product over multiple years). He has also been celebrated at the International Chocolate Awards and Salon du Chocolat.

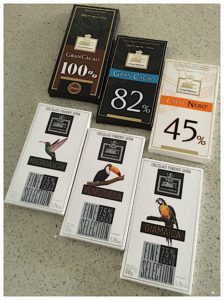

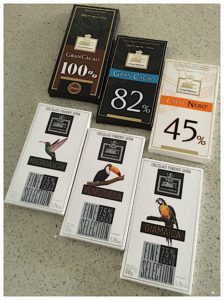

The Lattenero 45% is one such celebrated creation, winning the Golden Bar award more than half a dozen times. The Lattenero range is unique in that it’s milk chocolate, made from a blend of select cocoa beans, with a higher than normal percentage of cocoa (45, 51, 63 and 70%). As I snap off a piece of the Lattenero 45% and put it to my nose, I find the aroma to be pleasant. Sweet but the cocoa elements still come through sufficiently, unlike mass produced milk chocolate. I place it on my tongue and let it melt. It’s rather smooth on the palate and the taste is milky, with hints of cocoa flavour. For a milk chocolate bar, I find it to be well subdued, as it should be. It’s just the right combination of cocoa, milk and sweetness.

The Gran Cacao 73% is another celebrated creation but, as a dark chocolate enthusiast, I opt instead for the Gran Cacao 82%. The aroma is heavenly. Strong, toasty and with the slight hint of nuttiness. These carry through on my palate, as I place a piece on my tongue. There is an initial hint of acidity, then the flavours open up – nutty, toasty and just a trace of berries at the end. Thumbs up, I say?

As I’m walking past the cashier, I catch a glimpse of a familiar face. Then, it hits me! It’s one half of the Slitti brothers! I walk up to shake his hand and ask if he is indeed Andrea. He looks at me, a little puzzled and corrects me. It’s in fact Daniele, the “coffee” brother. I speak excitedly but he shakes his head, beckoning to one of the ladies behind the glass showcase. The lovely Giada (meaning jade in Italian) comes over and introduces herself. She acts as the interpreter as I tell Daniele about my excitement at meeting him, visiting Slitti’s HQ as part of our Tuscan Chocolate Valley adventures and my experience at the Amedei chocolate tour. They tell us to come back in the new year, when Slitti too will commence running a tour at their factory, just behind the shop.

Giada then leads me to the glass showcase to assist me in picking out a selection of pralines, ganaches and giandujas. In the midst of doing this, Daniele strolls over and presents me with a prepackaged bag of more handcrafted chocolates. It’s complimentary, he says through Giada. I refuse but he insists, so I accept it graciously.

As we are about to head off, Giada asks the all important question:

Who is better, Amedei or Slitti?

I smile and evade the question. How do you compare apples and oranges? Each is unique in her and his own way – one is a master at single origin creations while the other is a master blender. Both are artistic and creative, but in their unique ways. I think you are both deserving of your accolades and achievements, and should be sufficiently proud to be representing the Tuscan chocolate industry on the world arena.

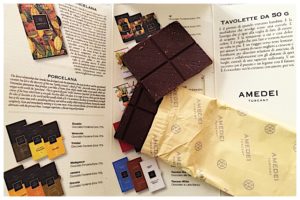

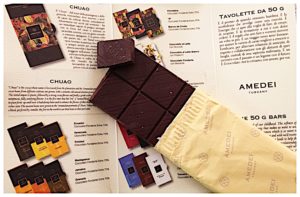

With this knowledge in mind, I sought to find out for myself if the Amedei Porcelana, and its sister bar, the Amedei Chuao, made from prized Criollo cocoa beans derived from the famous Chuao region of Venezuela, lives up to its reputation.

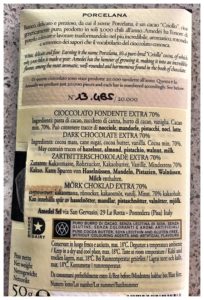

With this knowledge in mind, I sought to find out for myself if the Amedei Porcelana, and its sister bar, the Amedei Chuao, made from prized Criollo cocoa beans derived from the famous Chuao region of Venezuela, lives up to its reputation. The packaging is attractive and classy. The design is consistent with the Amedei theme, as seen on the painted walls of their headquarters, and the colours bring back fond memories of Tuscany. Each bar is apparently packaged by hand. The number on the back of the Procelana bar tells me that I’ve purchased bar number 13,485 of 20,000 for the year.

The packaging is attractive and classy. The design is consistent with the Amedei theme, as seen on the painted walls of their headquarters, and the colours bring back fond memories of Tuscany. Each bar is apparently packaged by hand. The number on the back of the Procelana bar tells me that I’ve purchased bar number 13,485 of 20,000 for the year. The Porcelana has a slight earthy nose. As it melts on my tongue, I find the texture to be both soft and gentle. The initial flavours are sweet and toasty, like roasted almonds. This gives way to the ever so mild hint of bitterness. And then the flavours disappear, leaving the palate fresh and ready for the next mouthful.

The Porcelana has a slight earthy nose. As it melts on my tongue, I find the texture to be both soft and gentle. The initial flavours are sweet and toasty, like roasted almonds. This gives way to the ever so mild hint of bitterness. And then the flavours disappear, leaving the palate fresh and ready for the next mouthful. The Chuao is surprisingly different. The aroma reminds me of mushrooms; not quite porcini, perhaps closer to swiss brown mushrooms. As it melts on my tongue, the fruitiness comes through prominently. The closest that I can think of is the flavours of caramelised figs, or Iranian dates. These flavours are slowly replaced by an earthy mushroom finish. Once the chocolate has disappeared, it leaves my palate with a slight but lingering tingle of bitterness.

The Chuao is surprisingly different. The aroma reminds me of mushrooms; not quite porcini, perhaps closer to swiss brown mushrooms. As it melts on my tongue, the fruitiness comes through prominently. The closest that I can think of is the flavours of caramelised figs, or Iranian dates. These flavours are slowly replaced by an earthy mushroom finish. Once the chocolate has disappeared, it leaves my palate with a slight but lingering tingle of bitterness. This was the scene that greeted us as we arrived at the headquarters of Andrea and Daniele’s family business, situated just outside the Tuscan town of Monsummano Terme. Originally established by their father, Luciano, as a specialty coffee roasting business, Andrea and Daniele subsequently took over the reigns and expanded the business. Daniele further honed his expertise in blending and roasting coffee while Andrea decided to build on his fascination with chocolate, applying his artistic and creative flair. These days, Slitti Cioccolato e Caffe (chocolate and coffee) is well reputed not just in Italy, but as far away as Asia and Australia, for their quality, award winning chocolates and coffee.

This was the scene that greeted us as we arrived at the headquarters of Andrea and Daniele’s family business, situated just outside the Tuscan town of Monsummano Terme. Originally established by their father, Luciano, as a specialty coffee roasting business, Andrea and Daniele subsequently took over the reigns and expanded the business. Daniele further honed his expertise in blending and roasting coffee while Andrea decided to build on his fascination with chocolate, applying his artistic and creative flair. These days, Slitti Cioccolato e Caffe (chocolate and coffee) is well reputed not just in Italy, but as far away as Asia and Australia, for their quality, award winning chocolates and coffee.

Curbing my enthusiasm for the chocolates that are still to be discovered, hubby and I head straight to the cafe section for breakfast. We place our order for a caffe marocchino and hot chocolate respectively.

Curbing my enthusiasm for the chocolates that are still to be discovered, hubby and I head straight to the cafe section for breakfast. We place our order for a caffe marocchino and hot chocolate respectively. Once sated, we adjourn to the retail section. Where does one start? Systematically, I begin with the award winning ones. The Tavoletta d’Oro (Golden Bar) is acclaimed as the most important chocolate award in Italy, and as a testament to his mastery, Andrea has won a Golden Bar for different creations almost annually since the 2000s (sometimes for the same product over multiple years). He has also been celebrated at the International Chocolate Awards and Salon du Chocolat.

Once sated, we adjourn to the retail section. Where does one start? Systematically, I begin with the award winning ones. The Tavoletta d’Oro (Golden Bar) is acclaimed as the most important chocolate award in Italy, and as a testament to his mastery, Andrea has won a Golden Bar for different creations almost annually since the 2000s (sometimes for the same product over multiple years). He has also been celebrated at the International Chocolate Awards and Salon du Chocolat. The search for Trinci resulted in hubby and I arriving at the gated entrance to a factory, in a secluded industrial estate in Cascine de Buti, on a cool and rainy Tuscan summer’s day. We were expecting a shop or cafe! Instead, we are greeted by a lone cat. Disappointed and with no help from the website, which is mainly in Italian, I am ready to give up and move on. However, hubby persists and decides to step out of the car to buzz the intercom. Out comes a lady in white uniform. From the passenger seat of the car, I can tell that hubby is struggling to communicate with her. She goes back into the factory, emerging moments later with a small bit of paper. On it is scrawled a name of a shop and a town. Apparently, Trinci’s chocolates can only be purchased in 3 locations, one of which is a shop in the little known town of Bientina. The other two are in Milan and Florence.

The search for Trinci resulted in hubby and I arriving at the gated entrance to a factory, in a secluded industrial estate in Cascine de Buti, on a cool and rainy Tuscan summer’s day. We were expecting a shop or cafe! Instead, we are greeted by a lone cat. Disappointed and with no help from the website, which is mainly in Italian, I am ready to give up and move on. However, hubby persists and decides to step out of the car to buzz the intercom. Out comes a lady in white uniform. From the passenger seat of the car, I can tell that hubby is struggling to communicate with her. She goes back into the factory, emerging moments later with a small bit of paper. On it is scrawled a name of a shop and a town. Apparently, Trinci’s chocolates can only be purchased in 3 locations, one of which is a shop in the little known town of Bientina. The other two are in Milan and Florence. With some renewed vigour, we head there in the rain, in search of Trinci’s creations. Locating the shop is an effort in itself. We walk in to find some Tuscan wines, metal vats of pressed olive oil and regionally harvested honey. Unfortunately, it is slim pickings of Trinci’s chocolates. We are told that the range and quantities stocked are minimal, due to the summer weather. Oh boo:( We purchase a bar each of what’s available – 75% dark chocolate with cocoa nibs and chilli (peperoncino) and 75% dark chocolate with cocoa nibs and Tuscan beach honey (miele della spiagggia).

With some renewed vigour, we head there in the rain, in search of Trinci’s creations. Locating the shop is an effort in itself. We walk in to find some Tuscan wines, metal vats of pressed olive oil and regionally harvested honey. Unfortunately, it is slim pickings of Trinci’s chocolates. We are told that the range and quantities stocked are minimal, due to the summer weather. Oh boo:( We purchase a bar each of what’s available – 75% dark chocolate with cocoa nibs and chilli (peperoncino) and 75% dark chocolate with cocoa nibs and Tuscan beach honey (miele della spiagggia). The dark chocolate with chilli bar has the distinct, pleasant, almost sweet aroma of well roasted cocoa beans. I chisel off a small piece and place it on my tongue. It doesn’t melt that easily, due to the high content of ground cocoa nibs. In fact, the nibs mask the ability to truly savour the texture and mouthfeel of the chocolate. And the chilli – there is a lot of it! I didn’t know that Italians had this high a threshold for spiciness. I find the chilli to be over bearing. I would not rate this as a personal favourite.

The dark chocolate with chilli bar has the distinct, pleasant, almost sweet aroma of well roasted cocoa beans. I chisel off a small piece and place it on my tongue. It doesn’t melt that easily, due to the high content of ground cocoa nibs. In fact, the nibs mask the ability to truly savour the texture and mouthfeel of the chocolate. And the chilli – there is a lot of it! I didn’t know that Italians had this high a threshold for spiciness. I find the chilli to be over bearing. I would not rate this as a personal favourite. During the roasting process, the shells of the cocoa beans separate from the kernels. The de-shelled kernels are more familiarly known as cocoa nibs. The cocoa nibs are winnowed by air, or using sieves or filters, to completely liberate the nibs from the shells.

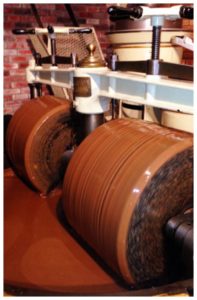

During the roasting process, the shells of the cocoa beans separate from the kernels. The de-shelled kernels are more familiarly known as cocoa nibs. The cocoa nibs are winnowed by air, or using sieves or filters, to completely liberate the nibs from the shells. Next, the cocoa liquor mixture is subjected to conching, which is regarded to be the all important step in the development of the flavour, smell and texture of chocolate. The mixture starts as a powdery mass and is kneaded using a machine known as a conche, for a period of several hours to several days. The continuous motion further refines the texture of the mixture and promotes flavour development through a combination of evaporation of volatile chemicals and acids, and oxidation. The end product is the working chocolate.

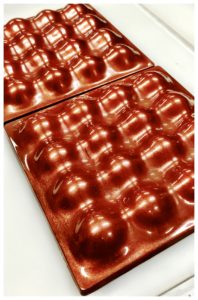

Next, the cocoa liquor mixture is subjected to conching, which is regarded to be the all important step in the development of the flavour, smell and texture of chocolate. The mixture starts as a powdery mass and is kneaded using a machine known as a conche, for a period of several hours to several days. The continuous motion further refines the texture of the mixture and promotes flavour development through a combination of evaporation of volatile chemicals and acids, and oxidation. The end product is the working chocolate. Tempered chocolate is now ready to be moulded into bulk bars, which may then be re-tempered to make finished chocolate bars, blocks, pralines and other moulded chocolates. The tempered chocolate may also go into another production cycle to produce buttons, pellets or blocks of couverture chocolate (which may sometimes be untempered).

Tempered chocolate is now ready to be moulded into bulk bars, which may then be re-tempered to make finished chocolate bars, blocks, pralines and other moulded chocolates. The tempered chocolate may also go into another production cycle to produce buttons, pellets or blocks of couverture chocolate (which may sometimes be untempered). What does “bean to bar” really mean? I trust that this has been clearly explained as we went through the intricacies of the chocolate making process.

What does “bean to bar” really mean? I trust that this has been clearly explained as we went through the intricacies of the chocolate making process.